It was an interesting day with lots of interaction and discussion between all of the participants and organisers—for example, my talk sparked debate about the future direction of driverless cars and potentials for alternative transport methods, and (separately) lots of questions about makerspaces and hackspaces. So much so that it was churlish to interrupt and instead I skipped some of the end of my slide deck so we could continue the conversation.

My slides are after the jump, including some very brief notes and also the ones that I skipped on the day.

Hello, I'm Adrian McEwen. I connect strange things to the Internet.

It's generally called the Internet of Things, and I wrote a book about that.

I also co-founded the makerspace DoES Liverpool.

I want to look a bit wider than purely the Internet of Things in this talk, and touch on some of how digital infuses more and more of the world.

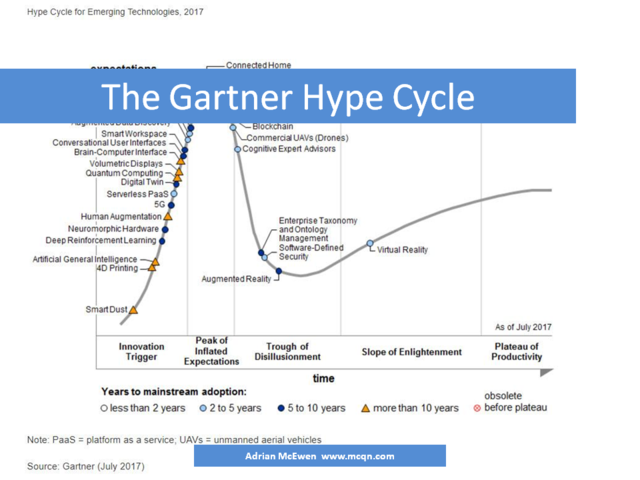

Every year, Gartner publish their "hype cycle" - a chart of the emerging technologies that they find interesting, and how they feel adoption is progressing.

I wouldn't hold too much store in the accuracy of the predictions, nor which technologies are, or aren't, on the list. However, it's a useful enough starting point if you're not working in tech, and the sequence of appearance; hype; disillusionment; (if it survives) adoption isn't the worst frame for how technologies join the mainstream.

The Internet of Things is usually equated to more and more sensors, and that's definitely a big part of it as the cost of such tech falls ever lower. For example, this river level sensor for Flood Network.

That lets us see things that are otherwise invisible, such as the air quality that's monitored by these Dustbox sensors that I helped develop for the Citizen Sense project.

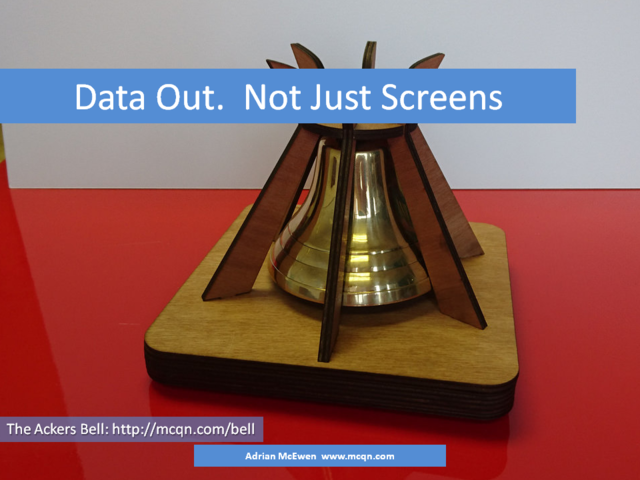

And IoT can also enable new ways of getting information out from the Internet. This is the Ackers bell, a WiFi-connected bell that rings to alert you to important (to you) notifications online. We'll be launching the kickstarter for it soon.

Connecting devices to the Internet also allows us to imbue them with new capabilities. The Good Night Lamp works as a light, but also as a calm notification to distant loved ones - giving them a window onto the patterns and activities of your daily life.

Laptops and phones are great general-purpose computing devices, but sometimes having a device that's focused on doing one job well - like Bakertweet here, for bakers with messy hands to send pre-rolled tweets - make life simpler and unlocks new possibilities.

When we start combining a lot of that we can build things like driverless cars.

However, I'm not sure that the best answer to our transport needs is autonomous individual pods. That will be in the mix but I'd wager it will be something new that's enabled by the better tech, rather than existing-dominant-mode-with-some-smarts.

Likewise drones are opening up new options but this feels more of a marketing gimmick than a real widespread solution to deliveries.

Something like this, the bike hire scheme in Liverpool, shows the sort of alternative I'm thinking of. The network and sensors enable new models that don't really look like they're "tech" solutions at all.

From the makerspace side, new tools are broadening and democratising production.

The hobbyist and prosumer level 3D printers are moving beyond toys and into providing useful output.

Microcontroller boards like the Arduino...

...and the Raspberry Pi, coupled with the openness and sharing of the communities around them, are enabling more experimentation with electronics and computing.

Subtractive manufacturing, such as laser-cutting...

...CNC routing...

...and CNC milling is also available to an ever wider audience.

And that unlocks new ways of arranging how we build products. Systems like Opendesk.

Or Wikihouse, which are shipping the designs rather than the finished product, and relying on more local, distributed manufacturing facilities.

With more and more open source tools and designs, some of the new business models aren't business models. This is Baylee, she used designs from Enabling the Future and the 3D printers at DoES Liverpool to print herself a new prosthetic hand.

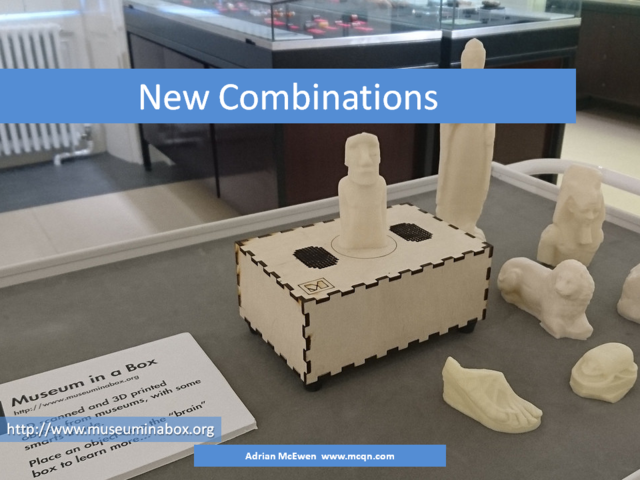

You can, obviously, also combine the Internet of Things with digital fabrication, such as in Museum in a Box, a startup I do the tech for, which uses NFC tags on a bespoke reader on 3D-scanned-and-3D-printed replicas of museum objects to play back audio tracks that tell you about the object you've chosen.

So is all of this new technology and possibility solely a force for good?

Sadly not. Alongside the opportunities for progress are opportunities for these new powers to be abused, and we need to guard against that.

Whether that's facial recognition and profiling from cameras added to billboards on the street...

...or the always-on microphones in our homes sending snippets of conversations to servers around the world.

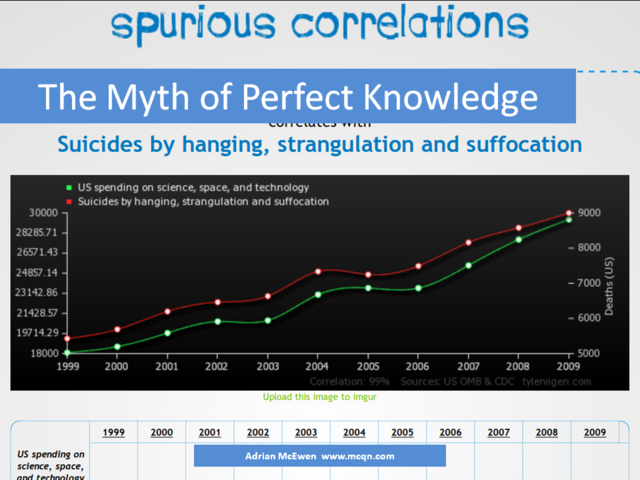

Some proponents of big data and IoT (wrongly) assume that the world can be perfectly captured and analyzed, if only they have enough sensors.

Or that the computer algorithms won't ever get caught out or make the wrong decisions.

We need to be having more conversations, as a society, about the choices we're letting the software engineers and startup entrepreneurs make. Working out how we can ensure that our apps and gadgets can be trusted. Making sure that we retain agency over the data being gathered about us and what happens to it.

It's a common refrain that the pace of technological development is getting ever faster, but is it really?

Tom Coates wrote an excellent blog post about that over a decade ago now. This is a quote from it, and I think sums up the issue nicely. You should only be surprised at the new technologies coming along if you haven't been paying attention.

To pick an example from my professional career, let's look at the development of the smartphone.

2007 is heralded, rightly, as the arrival of the smartphone, because that's when Apple launched the iPhone.

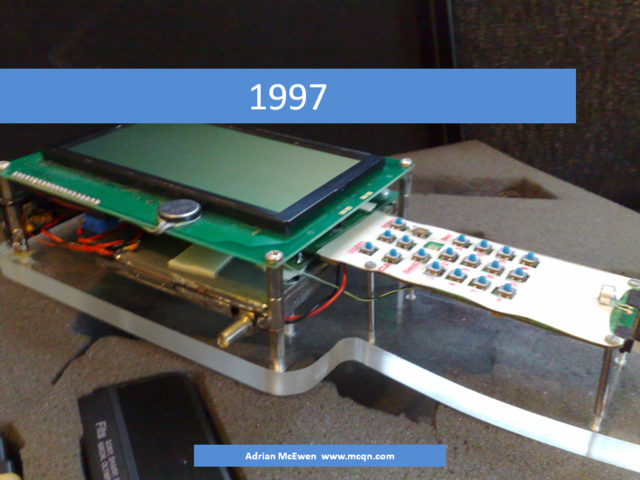

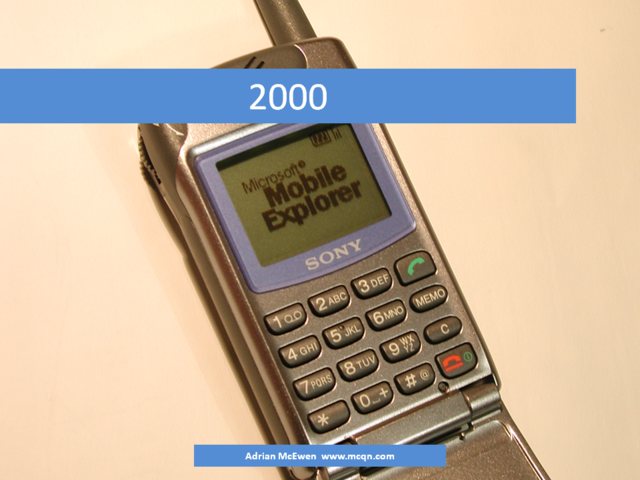

However, a decade earlier I was involved in building this. It's the first web browser running on a mobile phone.

Obviously that was the prototype that we used for development and demoed at shows. It took a couple more years to make it into a production handset, by which point we'd been bought by Microsoft.

There are a bunch more developments that fed into making the convenient computers-in-our-pockets that we have today (colour screens, widespread availability of WiFi, etc.) but there were at least ten years of hints before the iPhone.

So how should non-technologists (and technologists too, the field is too broad for us to assume we'll know all of it by default) keep an eye on what's happening? And how do we avoid some of the possible technological wrong turns and pitfalls?

I often return to this quote from designer Eliel Saarinen when thinking about designing products or systems. Thinking about the wider context in which the solution is placed will help to frame the ways in which it will be used and/or abused. Look for the unintended consequences of the new developments, then you can look for ways that you may be able to mitigate or prevent the undesirable ones.

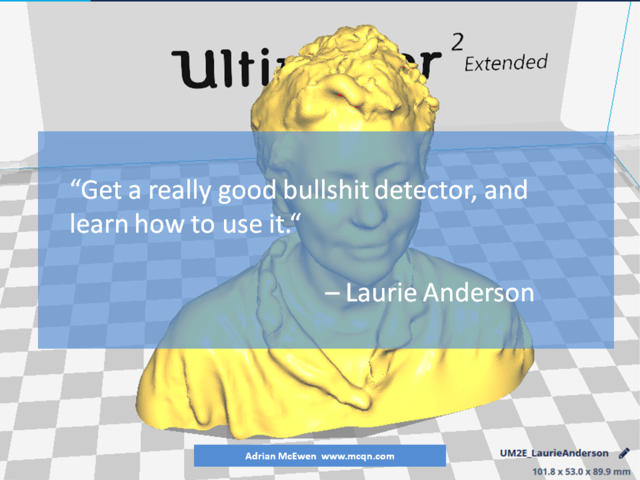

This is arguably the most important lesson in this entire talk. There are many, many people who will learn the latest buzzwords and try to pass themselves off as experts in them, hoping that you'll be too polite, or too embarrassed about appearing ignorant, to call them on it.

Any expert worth dealing with will be not just able to, but also happy to, explain any of the things they're proposing in terms that you understand. If they aren't, they're not an expert you should be hiring anyway.

Diversity in the teams you put together to build things, in the people you solicit opinions from, in the workplace in general will lead to building better products.

Do work that you're interested in, you'll enjoy it more and you'll do better work.

And be interested in things, in people. Russell Davies wrote a lovely blog post with some tips on how to be interesting. Have a read of that. The next couple of slides are mostly me channelling Russell, to be honest. (There's another tip, always cite your sources...)

Pay attention to the world around you. Social media has encouraged us to do this lots now, but the value is more in developing a curious approach to the world than it is in building follower counts.

Write about your interests or your industry or both. Don't approach it with a view to becoming a "pro blogger" or anything like that, that's a guaranteed way to remove any life from your writing. Write to help work out what you think, and improve how you communicate it with others.

If you must, start writing on Medium, but really getting your own domain and a blog there (Wordpress.com will do all the admin for you at reasonable rates) and owning your own little bit of the Internet is a much better idea. (The blog in the photo is McFilter, my personal blog)

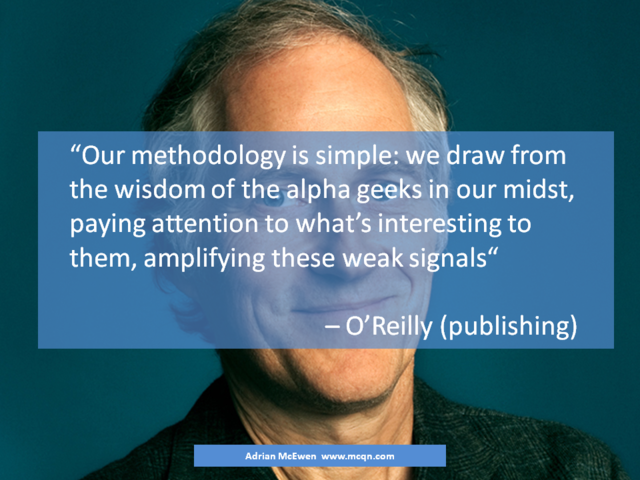

Seek out people whose work you find insightful or useful or who you think are doing something interesting...

...and keep up with what they're doing. Read their blogs, follow them on Twitter, or whatever social media systems they use. Their opinions on emerging technologies will help you decide what is really worth investigating and what is just getting hyped. The "alpha geeks" will investigate these things for fun and play around with it. If no-one is doing that, it's probably not interesting or going anywhere.

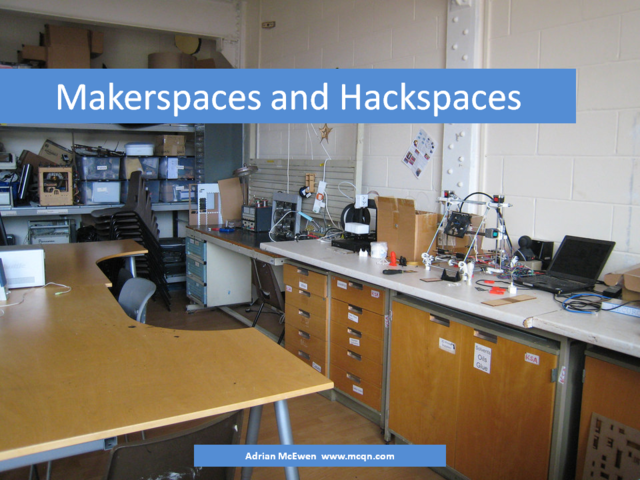

And if you want to seek out such people offline rather than on the Internet, you could do far worse than checking out your local makerspace or hackspace. www.hackspace.org.uk/ is a good starting point for finding one, along with Nesta's open data set of makerspaces from a couple of years ago.